1983 was a phenomenal year for genre and post-modernism.

Science Fiction in cinema found new peaks after the space opera box office spree of Star Wars, with Blade Runner and John Carpenter’s remarkable remake of The Thing.

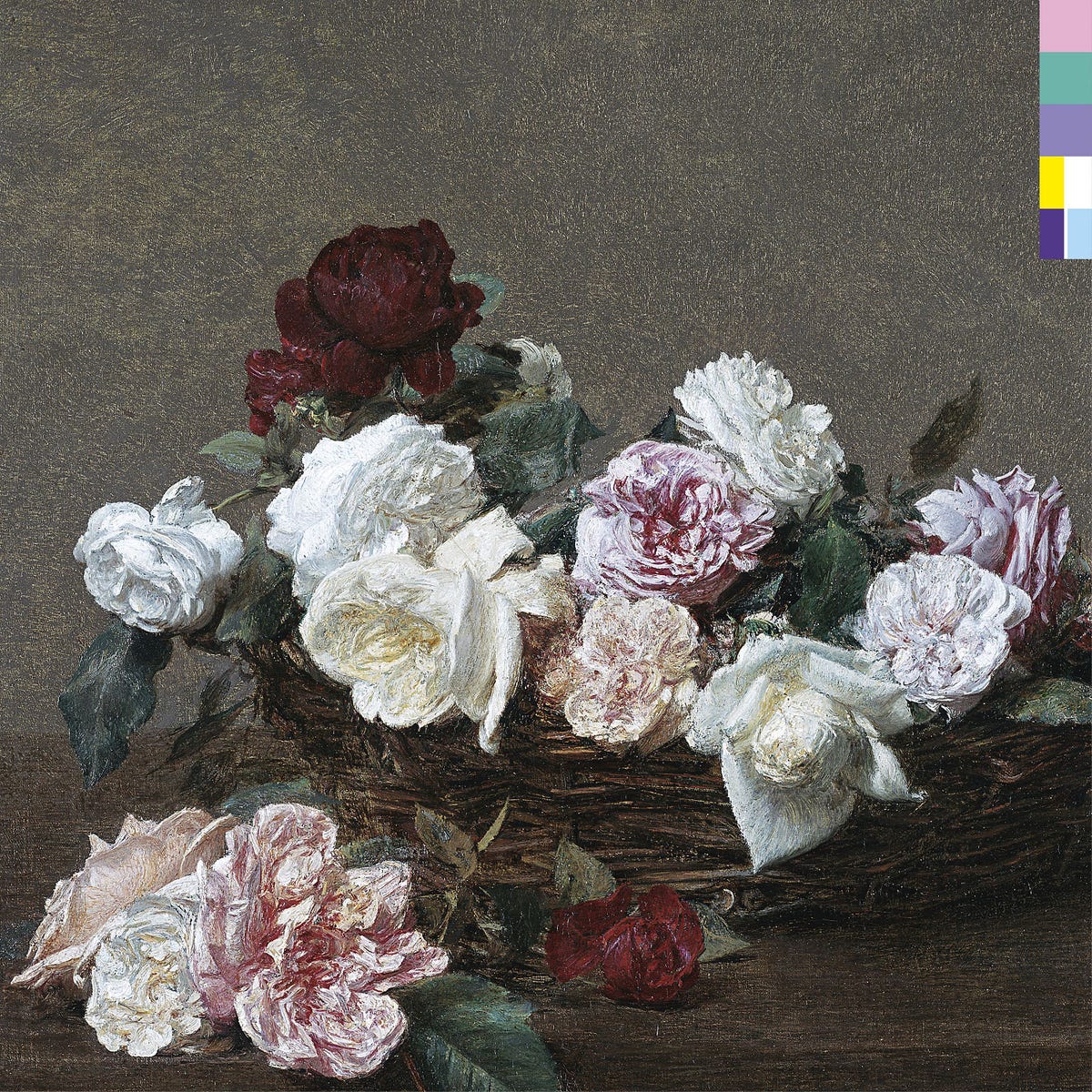

In music, punk was moving toward post-punk and new wave with The Cure’s Pornography, The Fall’s Hex Induction Hour, New Order’s Power, Corruption and Lies and so many records now regarded as classics.

Meanwhile, in the not-yet-mainstream world of comics, artists and writers toiled in relative anonymity. Making disposable product for kids.

Sure, Marvel was building its extended universe, which would later be ripe for plucking by former nerds turned studio executives.

And in Britain, caustic punk infected comics with cynicism and world-weariness.

But at DC, the staid home of Superman and Batman, a vanguard creative team was embarking on an ambitious publishing project. Guyanese artist Trevor Von Eeden and American writer Robert Loren Fleming were creating the seeds from which a medium revolution would grow.

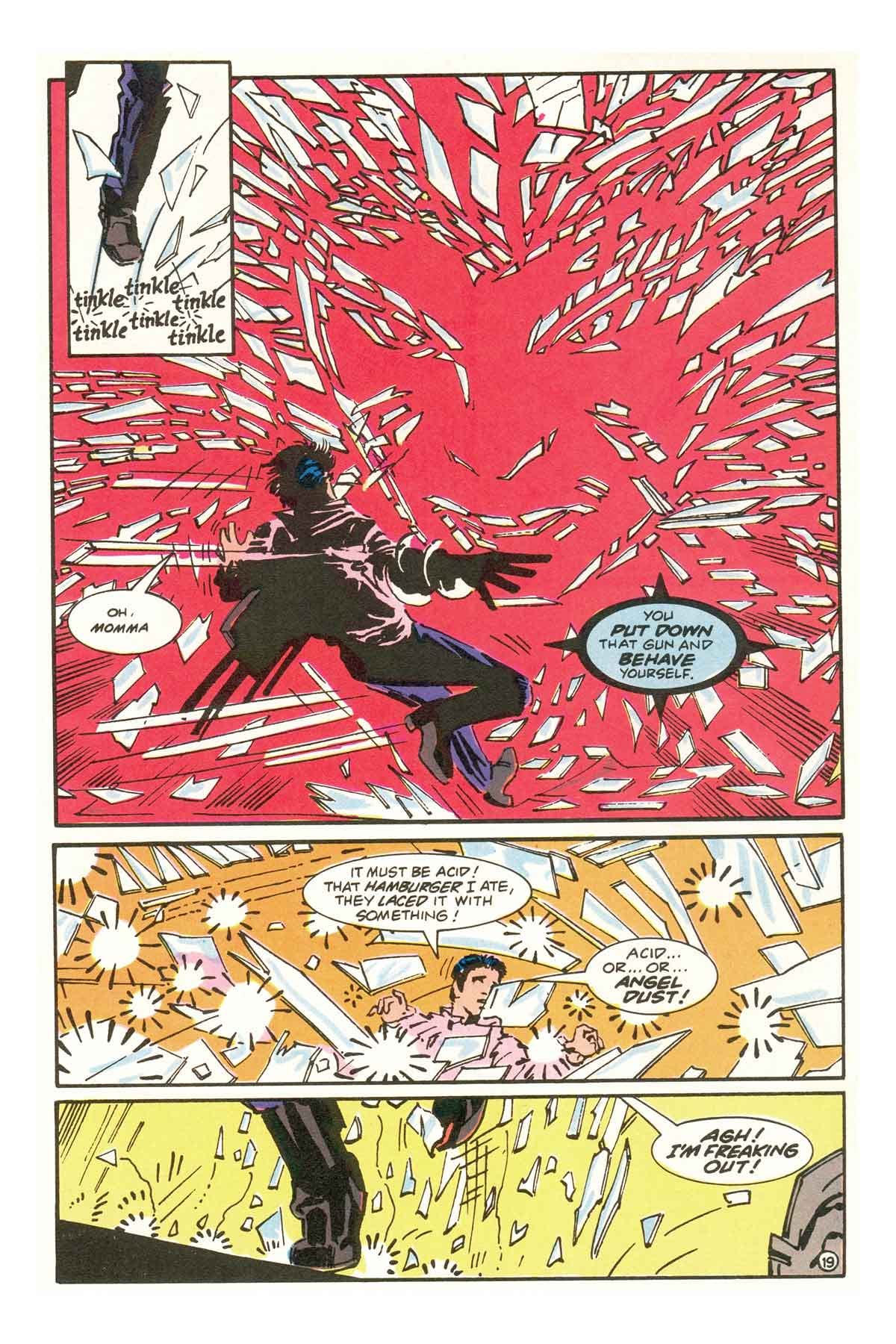

Thriller was one of the first comics where you felt the weight of unpredictability. Characters died. Even with reincarnation theory tossed around, people were beheaded, died in fires.

There was not the manufactured artificiality of deadline-driven pulp comics for kids. This felt not real but with heart and soul, like someone created it for the sake of story, almost for mythos, not to feed the maw of children’s endless need for play acting and comic costumery.

I was 13 when Thriller came out – I bought every issue through my comic book subscription service, mail order, because I wasn’t close enough to a comic book store.

The direct market – comics made specifically for comic book stores, not newsstand, was really only now getting up and running.

Thriller was $1.25, not $.60, printed on expensive Baxter paper, with whiter whites and brighter colors.

Thriller only ran for 12 issues (November 1983 – November 1984). Fleming left after #7, and Von Eeden left after issue #8. The series ran four more relatively discardable issues by writer Bill DuBay and artist Alex Niño.[5]

But those first four issues.

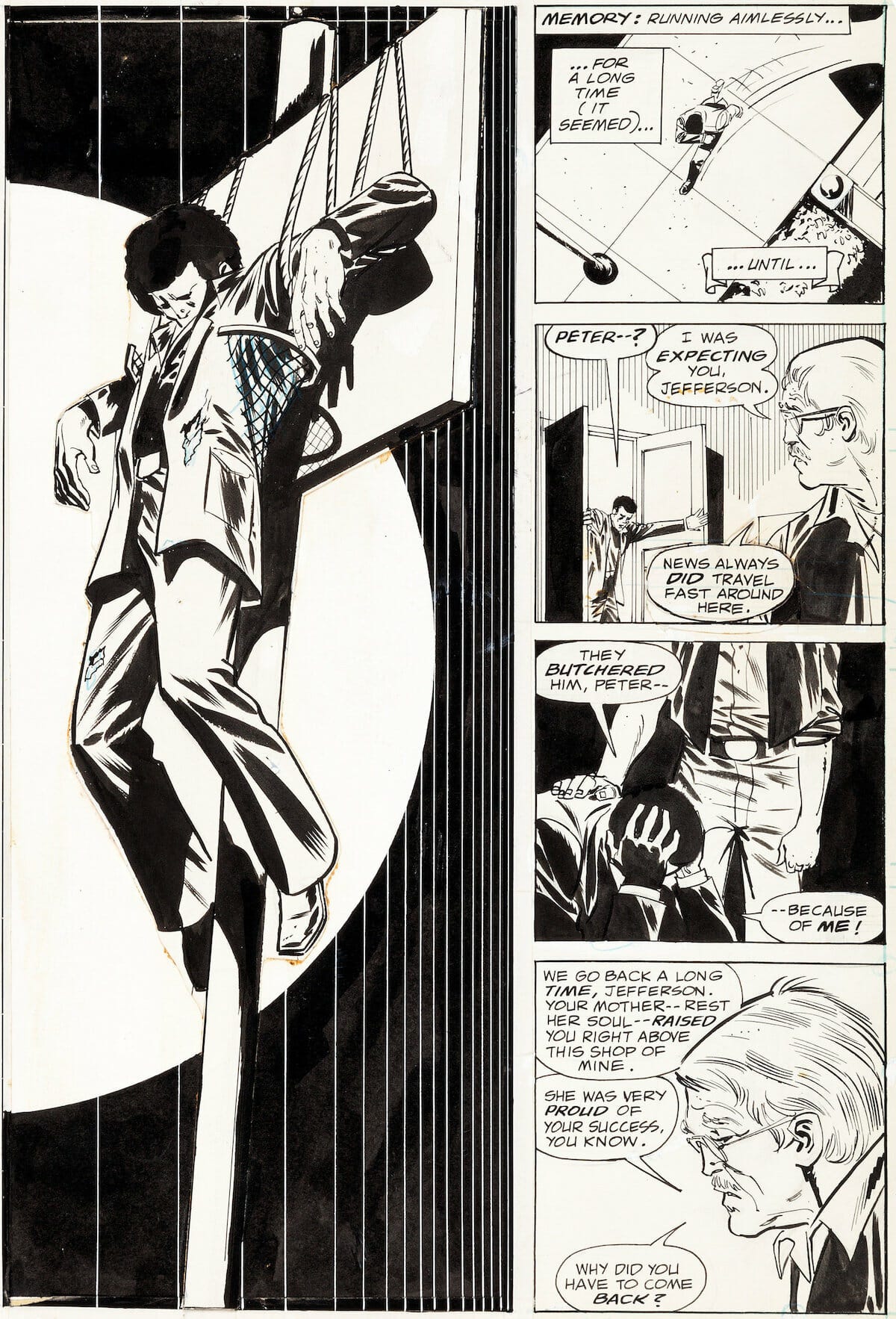

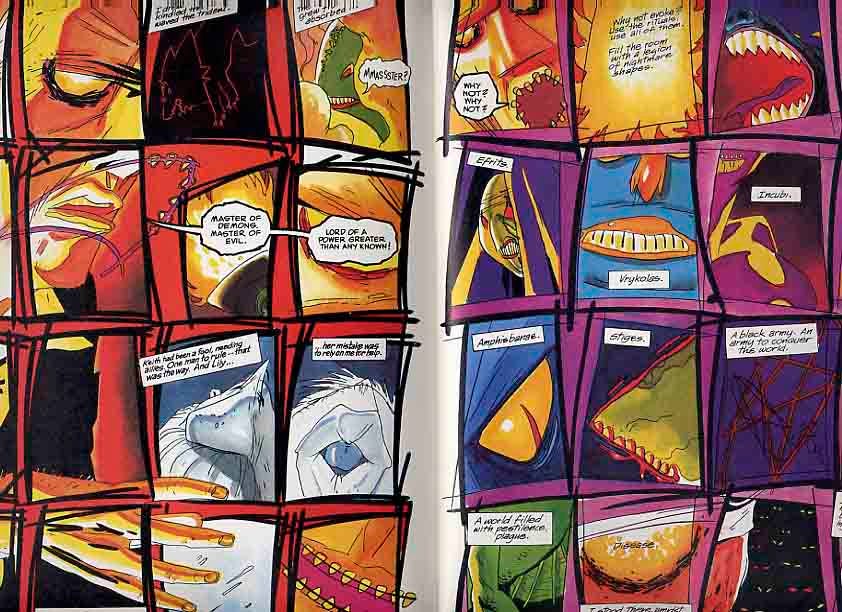

Von Eeden’s art had a scratchy, dynamic spaciousness. It was contained along thin pillars, or burst across the page for a real sense of verticality or angularity.

Experimental and cinematic, Von Eeden’s art was far ahead of its time. He used dynamic panel layouts, extreme close-ups, odd camera angles, and bold shadowing.

He was inspired more by European artists like Moebius or Milo Manara, and filmmakers like Orson Welles and the chiarascuro noir of John Alton, than his superhero contemporaries.

Von Eeden was the first black artist that DC Comics hired and one of their youngest, at 16. He created Black Lightning, and even appeared in a brief cameo on the TV show a few years back.

Von Eeden was from Guyana, and dating Lynn Varley, who would rise to prominence as the colorist on the ground-breaking The Dark Knight Rises with Frank Miller a few years later.

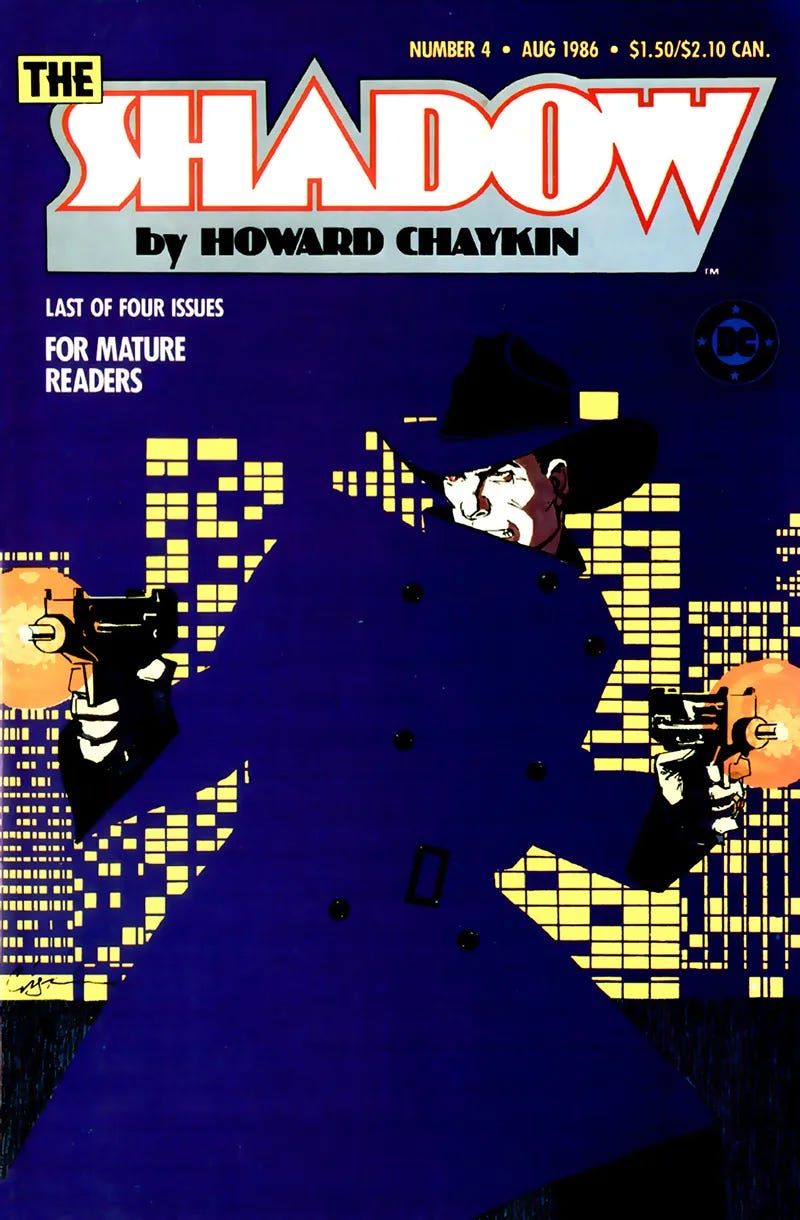

The only real parallels at the time would be some of the stuff coming out of First Comics, like Howard Chaykin’s satiric, graphically impressive American Flagg! (exclamation mark inclusive in the title) or the aforementioned Moore.

What is Thriller about? It’s pulp nonsense of course. A team of super agents who work for a godlike Angela Thriller and her husband Edward Thriller. Writer Robert Loren Fleming would describe Angela as “a cross between Jesus Christ and my mom.”

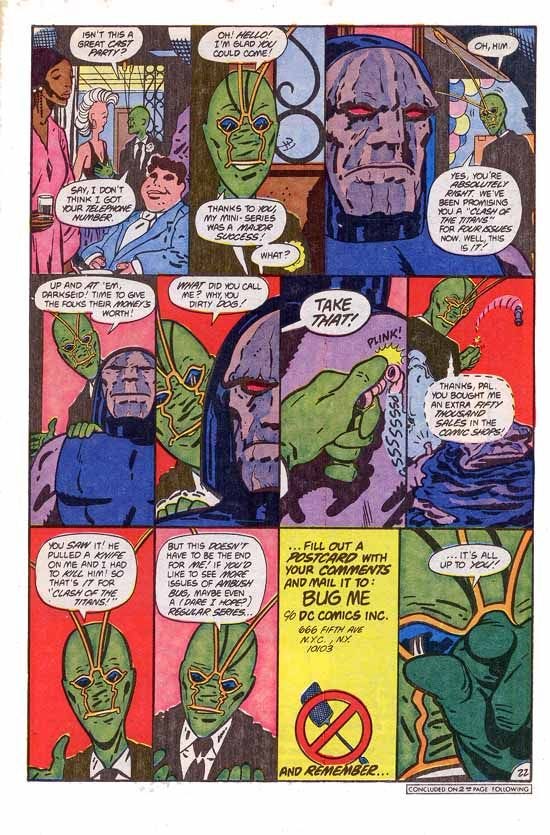

Loren Fleming was a new talent, often working with famed comics artist and writer Keith Giffen. They later adapted Robert Bloch’s Hell on Earth into a DC Graphic Novel, and also collaborated on the fourth-wall-breaking, anarchic Ambush Bug.

A new talent at the time, Fleming wrote Thriller with dense, elliptical narration and stylized dialogue. It was cryptic, poetic, and loaded with subtext.

Fleming used voice-over narration that often contradicted the visual action, adding psychological tension and complexity.

The characters spoke in odd, idiosyncratic ways that made them feel mythic or surreal, rather than "naturalistic." But in the way that a Doc Savage book limns the mythic.

In comics, Frank Miller had just reinvented Daredevil with his innovative graphics, drawn as much from Will Eisner as from Jack Kirby. Bill Sienciewicz was about to further pull comics into the future with his similarly scratchy, painterly The New Mutants the next year, 1984.

Those European comics, and Japanese as well, were exploding the formality and sameness of mainstream comic art, as Manara, Moebius, and the graphic Metal Hurlant made their mark on American creators.

From 1981–1984, both comics and film saw a notable rise in genre sophistication—post-modernism was bringing self-awareness to the horror genre via Sam Raimi and the shoestring brilliance of the scripts John Sayles was pounding out for Roger Corman, Piranha, The Howling, and Alligator.

Pulp ideas were taken seriously, narrative complexity deepened, and creators began challenging form and expectation.

This post-modernism, extending across film, music, comics and other graphic art was ambrosia, Prasada, nectar - pick your food of the gods - for a lonely 13 year old kid in the midwestern suburbs of Minneapolis.

Meanwhile, Fleming and Giffen were anarchically deconstructing comics in Ambush Bug. Giffen shared Von Eeden’s sense for scratchy dynamism, but played with the 12 or 16 panel page, breaking it where the narrative dictated.

And that science fiction graphic novel, while an acquired taste, is Giffen’s art taken to the formally inventive edge.

Remember, this was DC Comics! Home of Superman and Batman and Green Lantern.

What Robert Loren Fleming, Trevor Von Eeden, and Keith Giffen were doing in the early 80s was nothing short of groundbreaking.

However, they were also deeply enmeshed in genre.

And probably too formally inventive for mass consumers.

It would take the chilling power of Frank Miller’s Dark Knight and the caustic literary wordplay of Alan Moore — in the context of superheroes with capes and swamp monsters - to finally lift the medium toward the relative mainstream it lives in today.

Which is not to say comics are mainstream.

Movies about comics are mainstream.

Creators still toil in relative obscurity.

Thriller was, yes, thrilling, at the time. And now mostly lost to a few internet articles. I had to find a lot of material via the Wayback Machine.

But picking up these comics again, out of a dusty box in the closet, still securely wrapped in plastic bags and boards, I remembered how vivid and challenging the medium could be, in 1983, or now.

This is Are You Experienced and I’m Nick Tangborn. Thanks for reading! You can find me at nicholas@areyouexperienced.co

This thing is 100% reader supported. If you don’t feel like a paid subscription, a one time donation is always welcome!

And if you feel like sharing this story, I’d sure appreciate it.

A little too late but I found out this morning, regarding my Substack piece about the innovative DC Comic Thriller from 1983, that editor Alan Gold actually offered Thriller to Alan Moore after Fleming left! To wit: "Here's a fun aside. Alan Moore volunteered to take over as writer, but I stupidly stuck with the writer Dick (Giordano) gave me. I saw it as a matter of loyalty. Having been a freelancer for about 10 years (moonlighting as a copy editor when I worked in book publishing), I couldn't warm up to the idea of firing a freelancer. As a result, Karen Berger got her big break with Swamp Thing and I went nowhere (as I deserved, having turned Thriller, among others, into a mediocre bore)."