Danse Macabre At 45

Does Stephen King's treatise on the horror genre hold up?

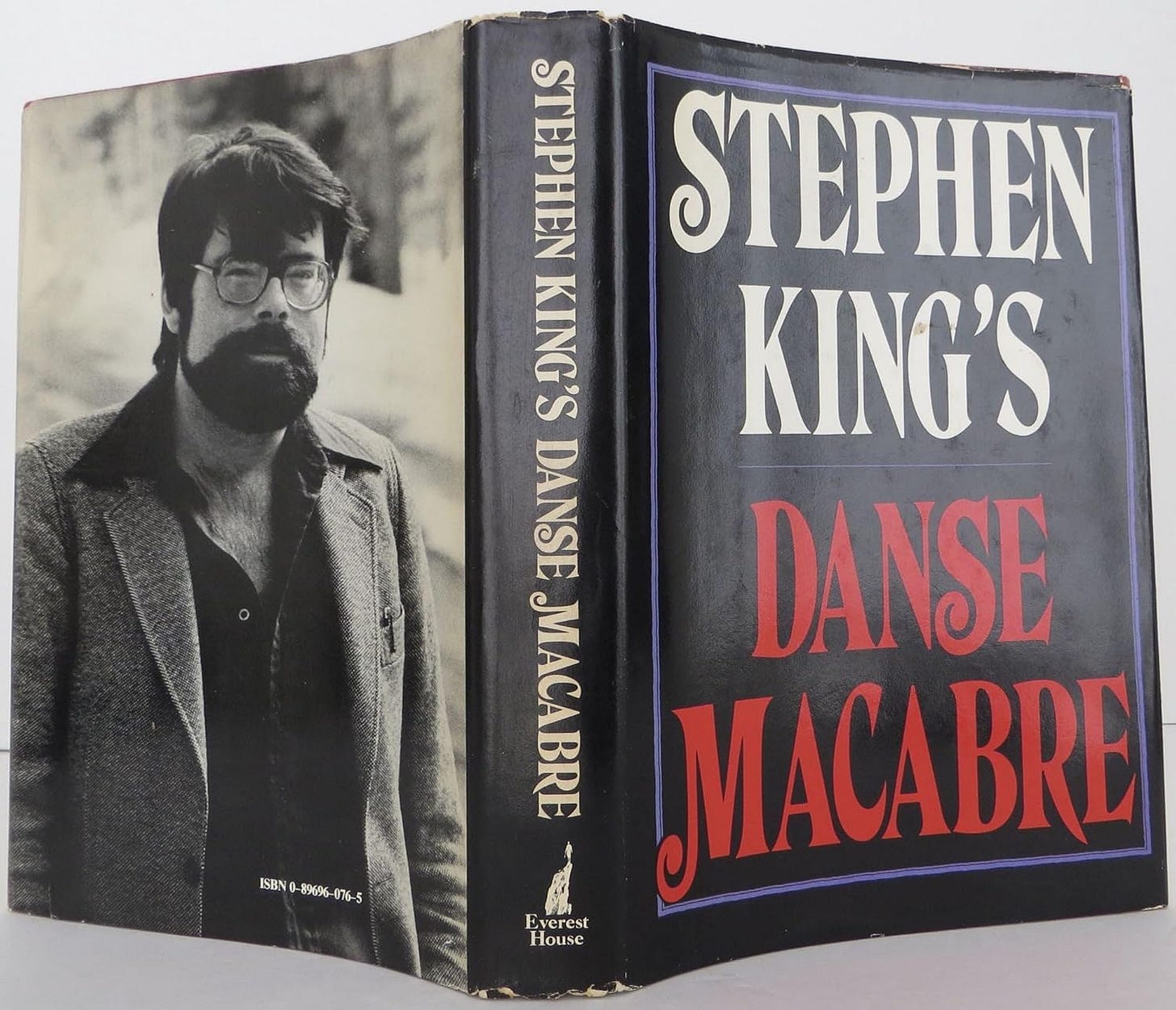

Danse Macabre, Stephen King’s first non-fiction book, and his treatise upon the horror genre, is now 45 years old.

As I head into writing nearly exclusively about horror, I thought I’d take it for a spin and see how its insights hold up, whether King’s take on horror in 1980 was consistent with contemporary horrors.

I thought, most of what had been taboo in 1980 was probably old hat by now. And who in 2025 listens to radio drama?

Except now we call them podcasts.

I was surprised then, how a lot of what King had to say was evergreen.

But also, how in explicating the lines between different types and distribution systems of fear, King laid bare his own innate understanding and, crucially, colossal blind spots.

King makes some fairly heavy ground rules and distinctions for horror over the course of the book.

“Terror on top, horror below it, and lowest of all, the gag reflex of revulsion.”

“If you can terrify, terrify. If you can’t terrify, horrify. And if you can’t horrify, go for the gross out.”

This, then, is the presiding nature of the horror story, the delivery mechanism.

There are two sides to horror itself, King writes: The gross-out, and the phobic pressure.

The phobic pressure is the terror we feel at a spider, a snake, impending death.

The gross-out is just that - gore, limbs bending the wrong way, death, especially, as King says, “the Bad Death.”

Nobody wants the Bad Death.

The monster is the aberration, and the horror writer is “the agent of the status quo.”

I don’t think he means the rock band.

Allegory and catharsis are the base metals of horror.

King was teaching English at the time. And so his exegesis (I swear I will stop using words like this) is fueled by this sort of theorizing; his hypotheses unfolding like an origami polyhedron that opens into smaller shapes nested inside one another, each transformation exposing new geometry.

Most horror fiction, he says, can be reduced to 3 archetypes plus 1. The Vampire, The Werewolf and The Thing Without A Name. Plus one is The Ghost. (I’m not clear on the whole plus one thing, but we’re talking archetypes so let’s hear it.)

The werewolf is the killer gone animalistic- Edward Hyde, Hannibal Lecter and of course The Wolfman.

The Vampire is the blood drinker and the flesh eater, from Dracula to the Living Dead. And the Thing without a name is the Mummy, the Frankenstein Monster, the Cthulhu mythos.

The Ghost of course is just that, the haunting in The Haunting, The Innocents, The Turn of the Screw.

And just when you think he’s going to box himself in, he adds to the archetypes with text and subtext, including sections about the political polemic horror film, the technology horror film and the social horror film.

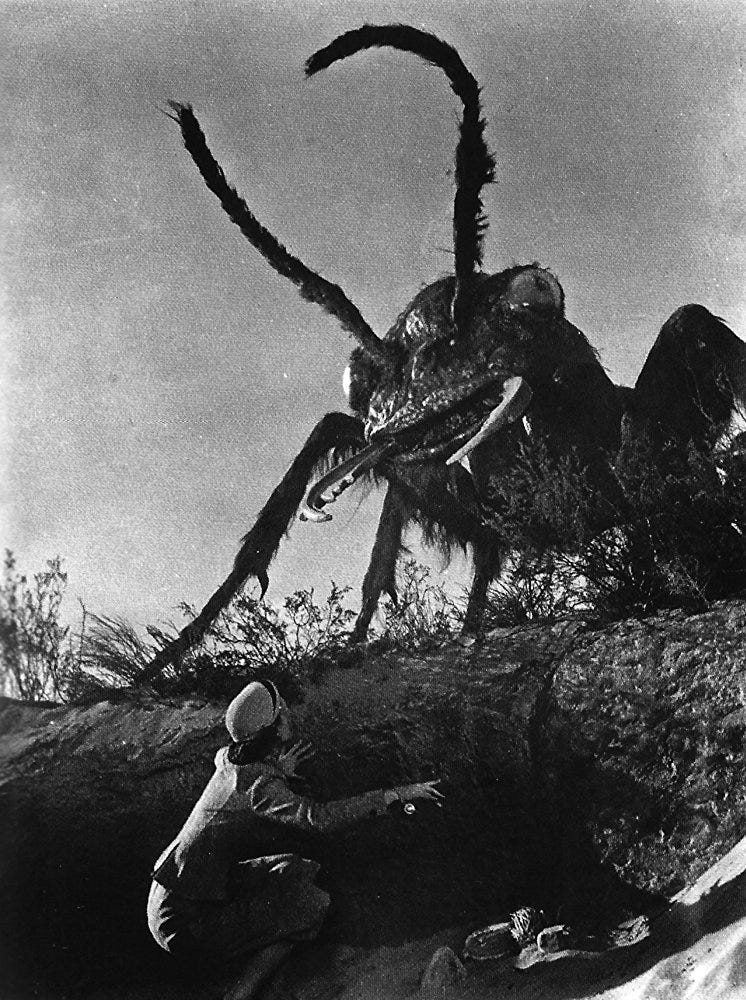

As the book unfolds we get the fairy tale horror story, stories told in the dark. We get horror movies, horror radio, horror fiction.

King’s concern is where the low trash meets the high art.

In horror, he writes, “the art is not consciously created, but rather thrown off, as an atomic pile emits radiation.”

And here we come to the nexus, speaking about The Amityville Horror: “As horror goes, Amityville (Horror) is pretty pedestrian. But so is beer, and you can get drunk on it.”

In King’s analysis he shows us his innate understanding and mastery of horror, but also his weaknesses and blind spots.

He talks in the same section about the fragile nature of the suspension of disbelief in horror — weighted like a zeppelin, but if it pops - or is seen - like the zipper up the back of the monster - it deflates heavily

He decries Cat People for its set-bound lack of realism, and talks about the power of Lovecraft never showing the monster in full,.

But meanwhile, and here is the crux with King, he says he will always open the door and show you the monster, because if it fails, it’s simply back to the drawing board.

And there is his hubris and his weakness laid bare.

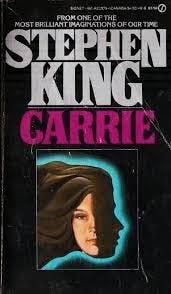

I read a lot as a kid, and the first author I really cottoned to was King, reading Carrie in its entirety in about a day and a half at the impressionable age of 10. Immediately, I went to the used bookstore in our neighborhood and picked up every other Stephen King book I could find: The Shining, the collection Night Shift, The Stand, Salem’s Lot.

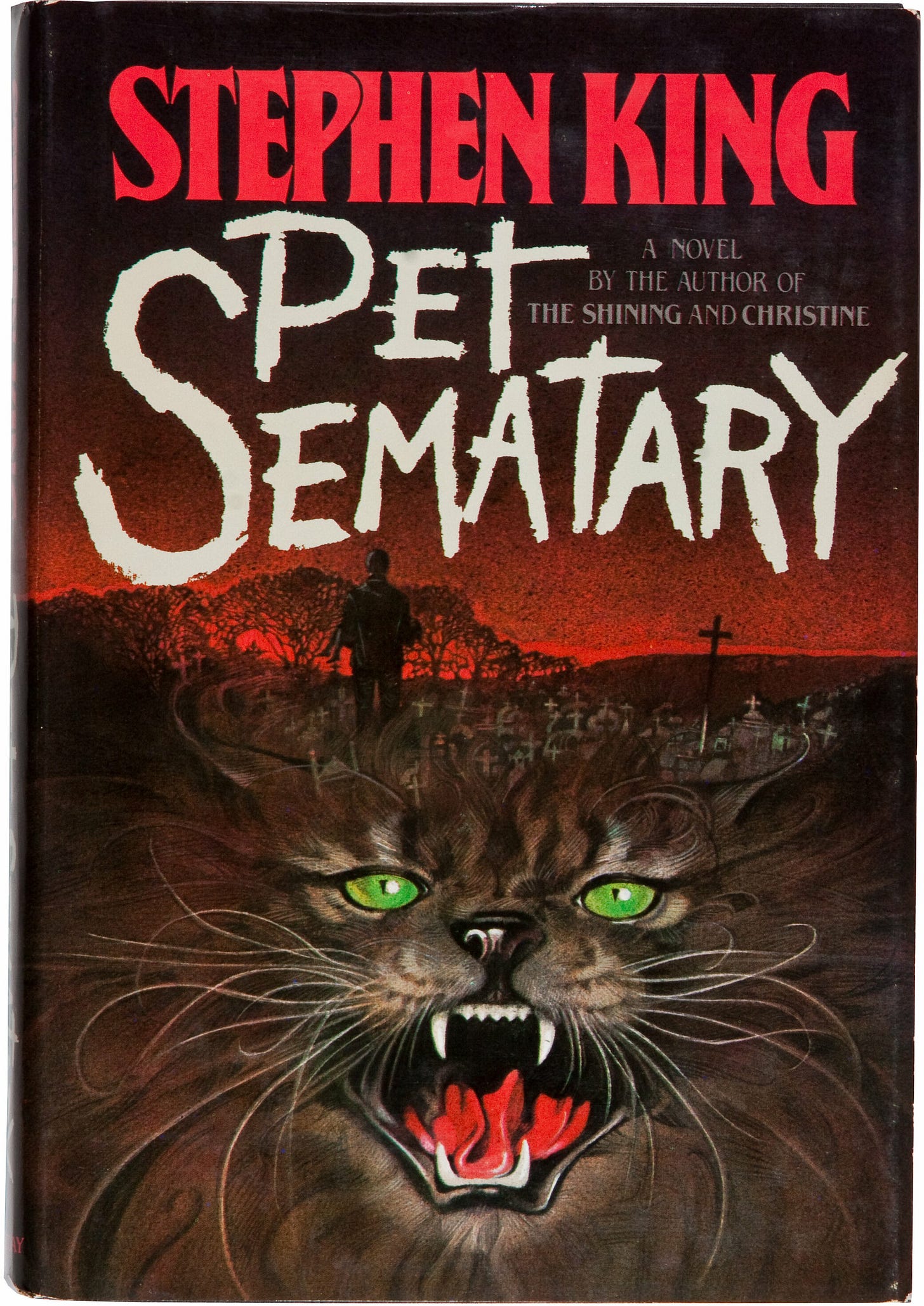

Christine and The Dead Zone followed in short order. And from there my parents had standing orders to get me the new Stephen King for Christmas, which they dutifully did. I remember reading Pet Sematary on the floor of my uncle Butch’s house in northern Minnesota, outside were wooded trails and wildlife of every kind and a distant treeline where you could just imagine the path to the pet cemetary in a dark, hollowed out spot.

Night Shift got me. Rich stuff like “The Mangler” and “Grey Matter” and “The Boogeyman.” This was long before any of these were made into movies, or TV show episodes.

I fell asleep with the book in my hands and awoke in a nightmare where I was outside the house, a suburban house in the middle of corn fields on 3 sides and in the outskirts of Lakeville, Minnesota, taking our small Lhasa Apso (Benji, all dogs were required to be named Benji in the late ‘70s) for a walk.

Out of the darkness came a shrouded figure, which as it got nearer I realized was covered in dark black chalkboard. I was trying desperately to get back in the house or at least call for my parents. I couldn’t get a sound out. I couldn’t move. Trying to move felt like I had lost all energy and my arms and legs refused to cooperate. And the thing just kept getting nearer and nearer until I finally actually woke up, unable to get a sound out. And unable to move.

I didn’t fall back asleep all night.

Something in King’s conversational, supernaturally gross yet grounded storytelling had so tilted my brain that all my school anxieties (the chalkboard monster!) and generalized kid anxiety was at the surface.

And so a love affair of sorts started with the King of Horror. I drifted in and out of his books once I left for college. I have most of them. I can say there’s a good chunk of them I haven’t read yet – after a while his shtick can wear thin.

But the key books still work for me - Pet Sematary, the Stand (the original version, the Directors’ Cut was too much of a good thing), Bag of Bones, Misery, even Mr. Mercedes had its semi-guilty pleasures.

I remember a musician friend who made a point of decrying falsehood and inauthenticity in other bands, yet was hubristically steadfast in restraining his own noisiness and chaos via control freak production.

He was his own worst enemy. King has, of course, monetarily succeeded, but in his quest for high art, if he even is on such a quest, he cockblocks himself every time by showing the monster.

His over-production kills the mood.

When he is at his deftest touch it’s like the horror is subsidiary to the story, and not the driving force

Famously averse to Kubrick’s version of The Shining, King is probably the only person alive who prefers Mick Garris’s version with Steven Weber.

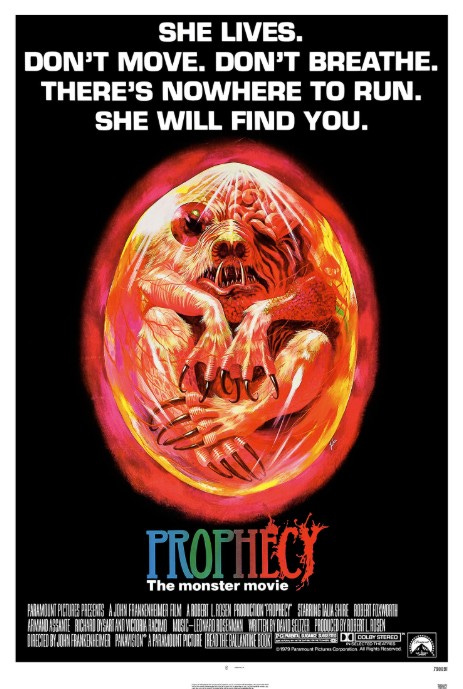

While his examples for political polemic - Dr. Strangelove and John Frankenheimer’s inside-out bear monster flick Prophecy - are very of-the-time, the message continues today in films like A House of Dynamite and Bong Joon-Ho’s The Host.

The social horror film of course manifests today in the work of Jordan Peele, whose Get Out could be an evolution of The Stepford Wives if you squint.

Meanwhile, technology horror films flood the market today, we are no longer limited to squalid outfits like the Farrah Fawcett-raping Saturn 3 or Julie Christie-impregnating Demon Seed.

On the basics, the plumbing and themes of horror, King’s antennae here were, surprisingly and across the board, receiving loud and clear signals that still resonate today.

It is in the pieces that he could not yet know in 1981 that things have really changed:

- Streaming TV and the renaissance of TV programming

- The internet and what it did for better or worse to fan culture

- Podcasts and the evolution of audio distribution

Where he is behind the curve, it is naturally a function of time, as he was writing 45 friggin’ years ago.

By the time we’ve wound our way to horror fiction, the book is on more persistently reliable and relatable ground: most of the books he writes about are still generally recognized as classics, especially The Haunting of Hill house by Shirley Jackson.

Some of the books he casually mentions would cost a small fortune these days. Good luck getting your hands on an Arkham House edition of Ray Bradbury’s Dark Carnival.

The books that King says we all have on our shelves are now hundreds of dollars on eBay or via Heritage Auction or vintage booksellers.

Even King’s own early work fetches more than it used to on eBay.

So yes, times have changed, and low trash has become collectors fodder.

And the dark and cheap stuff has become A24 prestige horror.

Danse Macabre has plenty to still offer.

It hasn’t aged like fine wine, but, as King says, it’ll still get you drunk

Thanks for reading Ghosts In The Machine! I’m Nick Tangborn. Get in touch with me at nicholas@areyouexperienced.co and please do let me know if you’re enjoying this thing.

This newsletter is free for everyone but those of you who pay keep the lights on and the book queue full. Much appreciated. If you can spare a few ducats, a paid subscription is very helpful.

See you next week.

Loooove swimming through the channel of King with you!!!

This was brilliant