The Harrowing Of Hell

And Other Funny Stories, or Welcome To Ghosts In The Machine

In the images of painter Hieronymus Bosch we see demonic figures, hell as landscape, Dante’s Divine Comedy made oil and tint. In Benjamin Christensen’s Haxan: Witchcraft Through The Ages (1922), we see Bosch’s figures made flesh.

In Francisco Goya, a witch’s sabbath feeds babies to a spectral goat, shades of Black Phillip in Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015).

In Salvador Dali, time itself is melted, corrupted, giving way to the surrealist films of Luis Bunuel and Alejandro Jodorowsky.

Dali even made a film with Bunuel, the influential eye-gouging short Un Chien Andalou. Which, in turn, inspired The Pixies’ Debaser.

“Got me a movie, I want you to know/

Slicing up eyeballs, I want you to know”

“The horror film is the most disreputable of the genres, the disrepute partly deserved, partly not,” writes the great film critic Robin Wood, one of horror’s most stalwart defenders.

“No genre is richer in potential, its thematic material rooted in archetypal myth and the darker labyrinths of human psychology and having analogies with dream and nightmare. Yet no genre lends itself more readily to debasement, whether through commercial opportunism or rhetorical pretentiousness.”

Horror’s inspiration and evocation is in classic literature, in fine art, in sociological commentary.

The tangled roots of horror intertwine with current events, evolving morals, and the cyclical way things stay the same.

It’s a Saturday afternoon in 1976 in Lynnwood, Washington. Rainy, it’s always rainy in this northern suburb of Seattle.

I was a chickenshit kid and I probably grew into a chickenshit adult, but at the time, I was especially un-durable. Scared of everything.

I wanted to watch Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. It was on the afternoon Chiller Theater package on the local KTVW Channel 13, if I remember correctly. The particulars escape me.

Except what doesn’t escape me is the instant dread I felt as Lou Costello unpacked the straw around the Frankenstein monster’s crate.

Stephen King talks about horror working on two levels: the gross-out, and the phobic pressure point. The latter was getting a workout for this six year old kid.

And as the monster and Dracula chased our bumbling leads around, I found a taste for classic horror.

Literature’s modern myths are built from the core fears of Dracula and Frankenstein, HG Wells and HP Lovecraft.

The horror film is by its very base nature allegorical and rich in literature’s symbology.

The vampire’s parasitism.

The Frankenstein monster’s science gone awry.

The zombie’s line between death and life, the zombie as betrayal by a loved one.

The alien’s otherness and xenophobia.

Horror stories can be literate art as functions of representation.

Like allegory.

Like metaphor.

Art teaches us a new way to look at an eternal human truth

The monster teaches us troubling realism brought to its extrapolated, poetic ends,

Great directors started in the scary movie trenches.

Francis Ford Coppola in Dementia 13. Jonathan Demme in Corman’s stable. Robert Wise servicing Val Lewton’s visions while cutting Citizen Kane.

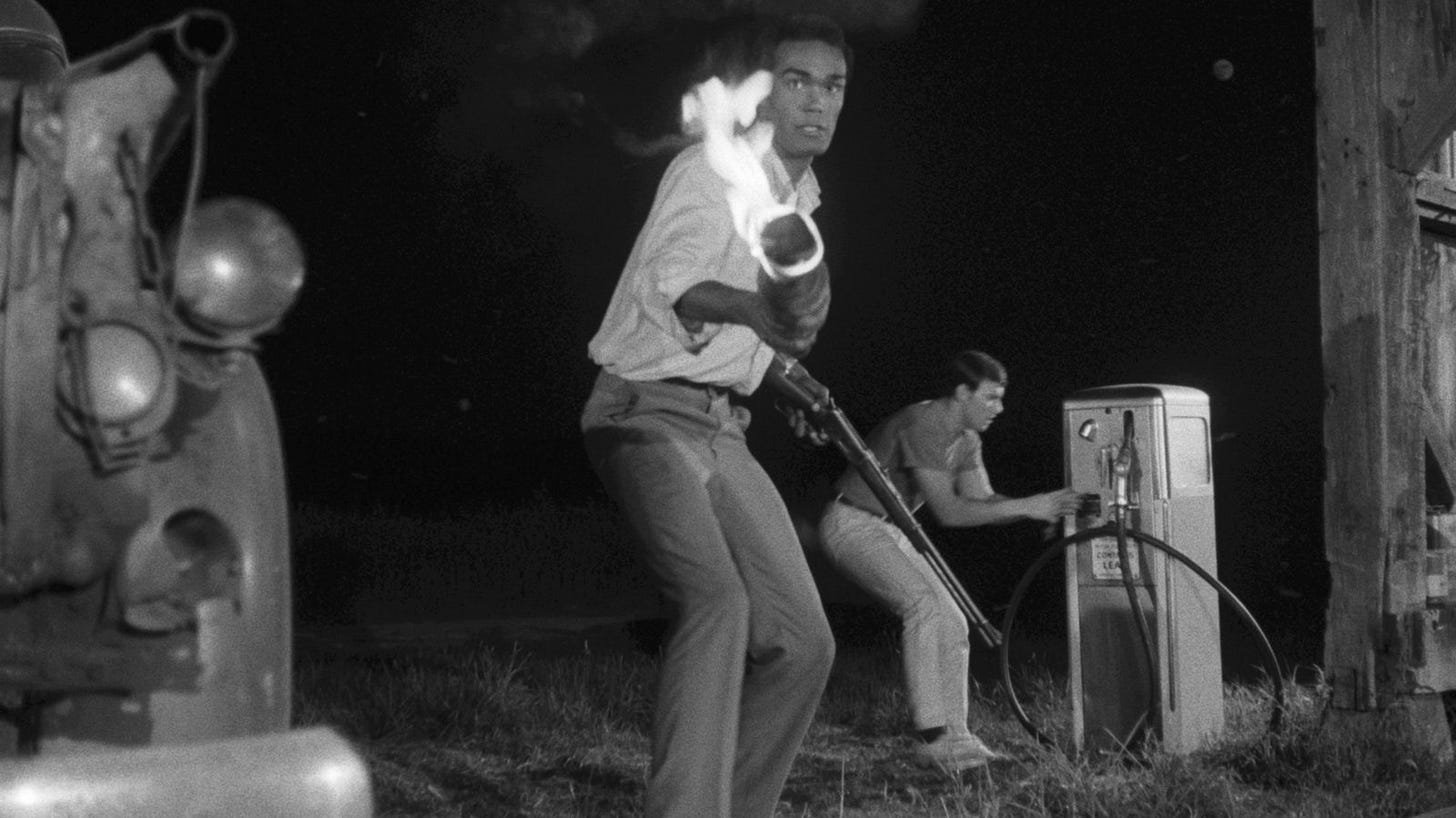

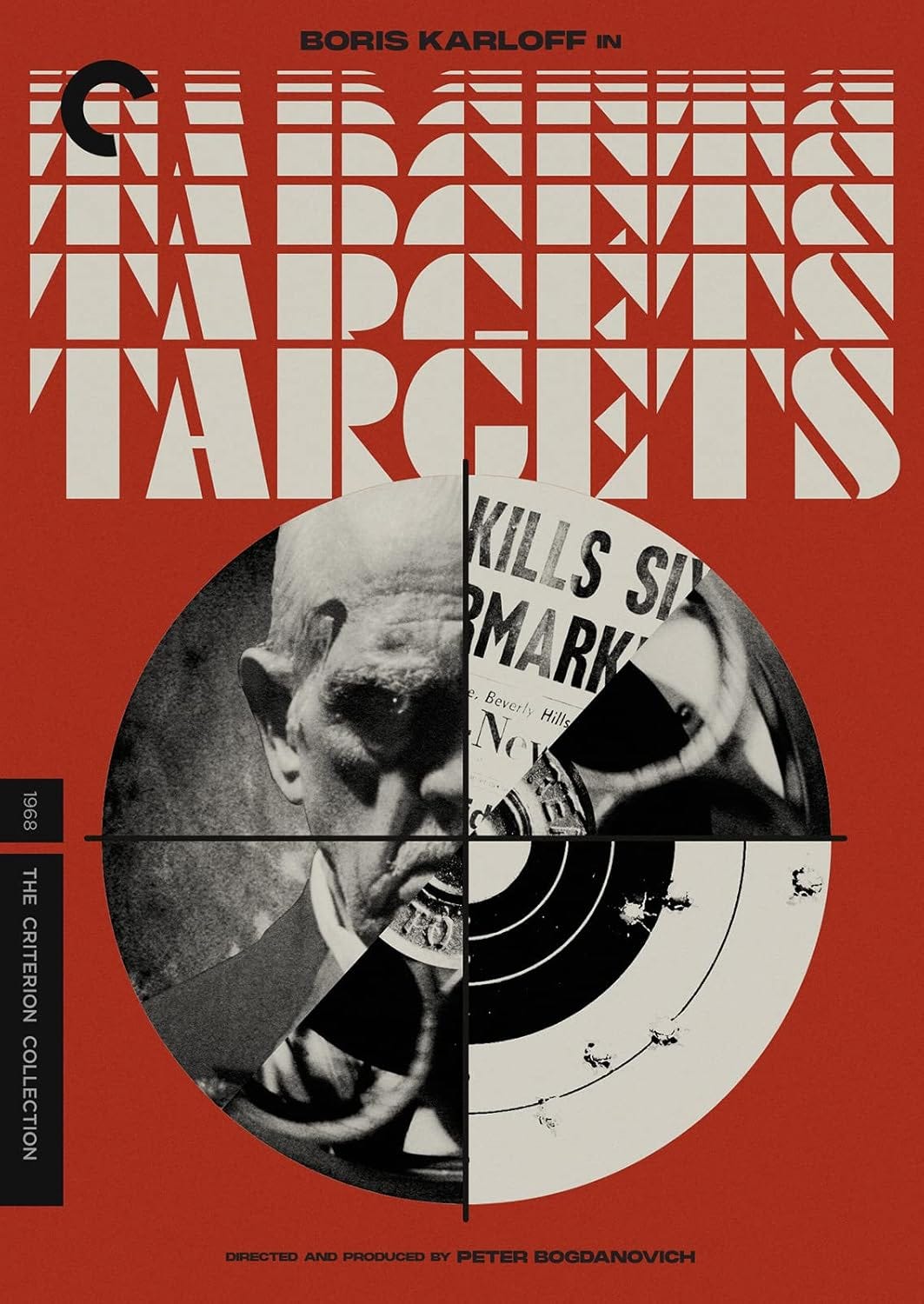

Roeg. Bogdanovich. Eggers.

Suspense and horror and demonic themes come directly out of fine art

Great horror movies can simply be great movies

Not all of horror is low class, cheap, tawdry trash.

Although a healthy portion of it is, in fact, just that.

Some of this is probably old hat to a lot of you.

And yet, I hope thru writing this to give a new audience a new crop of movies to investigate, or at least give the existing audience new perspectives on what may seem like old hat.

Or even suggest some films you may not yet know.

Stephen King writes, in Danse Macabre, a text I’ll come back to, that you can only truly know what you believe, what you feel about something, if you force yourself to put pen to paper.

Can I, ultimately, shine 55 years of horror culture obsession, starting with that afternoon matinee, meeting punk rock and country music and western literature and endless software startups and comic books and cult magazines and look at horror’s precedents and antecedents in a new light?

Horror is a distinctly primal pleasure and its pin pricks can be startling.

I will not lead you to dangerous territory without due warning.

But I will also not spoil worthwhile surprises for the sake of protectiveness.

Horror is meant to scare, to terrify.

Or sometimes maybe just to illuminate darkened corners.

Or make our worst fears conquerable.

I’ll show you beautiful gothic images worthy of fine art in the work of Michele Soavi (Dellamorte Dellamore), Alex de la Iglesias (Day of the Beast), Guillermo del Toro (Crimson Peak), to the bargain basement apocalypse of Lucio Fulci’s The Beyond, for advanced students or the obsessively intrigued only.

There are areas of horror cinema that I won’t readily tackle here — torture porn, cinemas of transgression, in-your-face cruelty, Mondo films which depict documentary style cruelty and death to animals and humans

That is not the forte of my kind of horror.

This is about the artifices that create fear and where they come from and what they evoke.

I hate to define this as what it is not, as that always seems like weak sauce.

But in pulling together the disparate strands of films I love, I feel it important to define the guardrails.

This newsletter will also tackle science fiction and fantasy, genres which often bleed into the culture of horror. The nerve sheathes are thin, the barriers weak, the surface tension easily broken.

I can’t say you will come out of this series a horror movie fan.

But to disregard horror is to miss out on one of the most vibrant, experimental, meaningful genres in all of cinema.

I’m going to do my best to guide you through some of the films I’ve found the most exciting, surprising, inspiring and otherwise compelling.

It’s 2025, in Austin Texas, and I’m watching Dr. X, a Lionel Atwill and Fay Wray pre-code programmer.

This is two-strip Technicolor horror at its earliest and wiliest.

In it, cannibalism post-mortem - at the morgue and on night of the full moon - drives the cops to investigate a cadre of mad scientists researching various suspicious epidemiology.

The presentation is stage-bound at best, with lurid greens and fleshy orange its only real palette. The moon shines artificially on Lionel Atwill and Fay Wray.

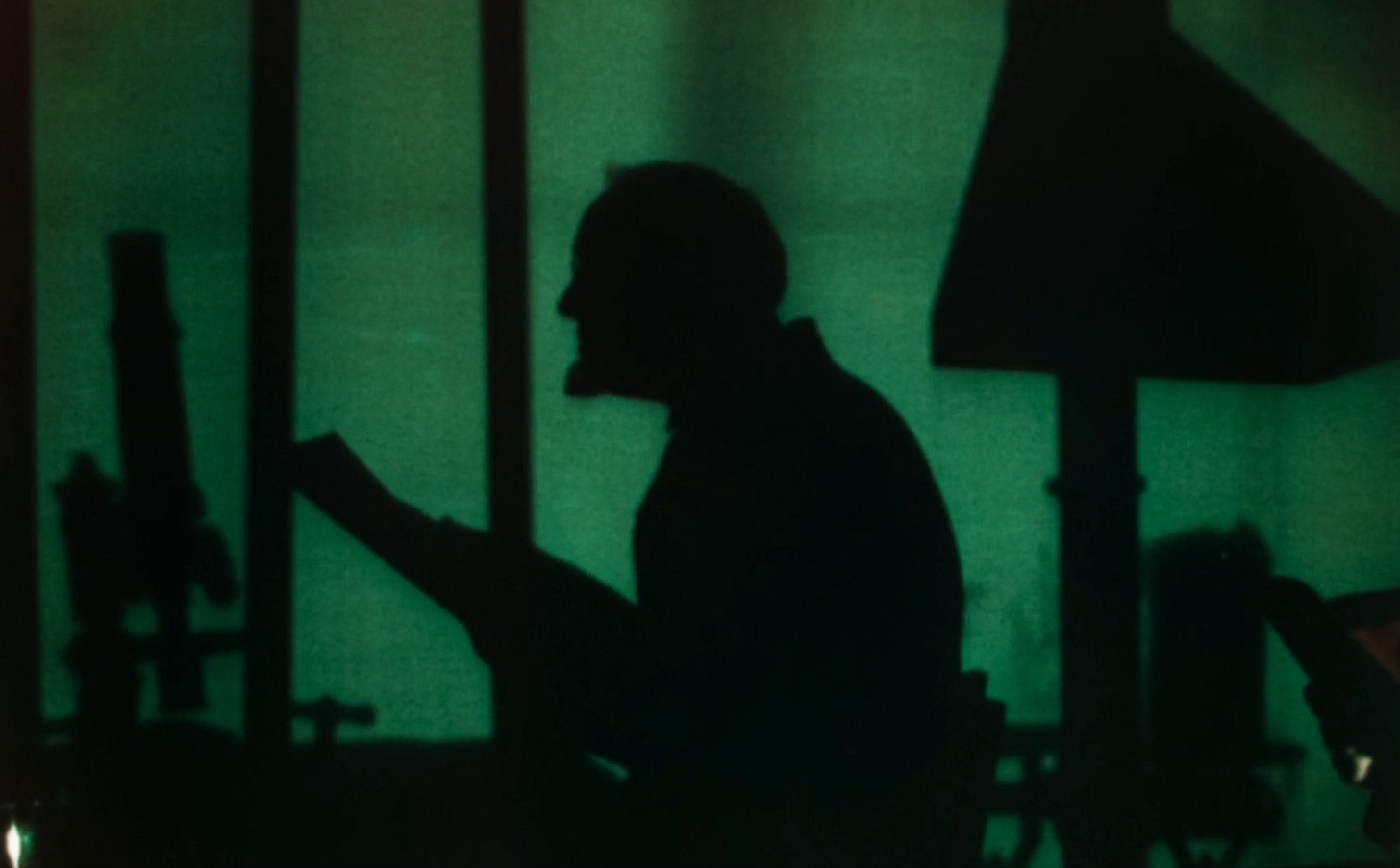

The doctors are introduced in visually suggestive terms, from the sleepless, gaunt amputee Dr. Wells, who is curiously studying cannibalism, to the Mephistophlean silhouette of Dr. Haines, all presented as various exemplars of psychomania.

This is base and nostalgic fun, some of the best kind.

The two strip color filming is by Gone With The Wind’s Ray Rennahan and directed by Casablanca’s Michael Curtiz, there’s no shortage of early film talent here.

I’ve had a lifetime of devouring horror films.

Of learning about Aesthetic. Craft. Metaphor. Trash. Base Culture. High Art.

I’m going to put Abbott and Costello and Dr. X’s high art and low trash through this funnel. And see what comes out the other side.

I’m Nick Tangborn and you’re reading my new Substack, Ghosts In The Machine.

Every week I’ll tackle genre films, cult culture, horror and sci-fi, high art and low trash.

Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein was also my introduction to horror movies and to the Universal horror stable (though I already recognized Bela Lugosi from Sesame Street!). We were watching it together as a family, the summer before kindergarten started. When Lon Chaney Jr starts to transform into the wolf man I got worried and told my mum that I probably shouldn’t be watching this. She looked at me and said, “Don’t worry, it’s going to start getting really funny.” And, she was right.

This is sick!!! I really enjoyed Danse Macabre, too. Looking forward to diving into more of your posts